Design and Aesthetics

The study of aesthetics and metaphor is deeply intertwined. Metaphor alludes to the truth without being truthful -- an abstract painting is the representation of the truth of something, but is not the thing itself, as Harman puts it. Aesthetics give us insight into the real without direct access to it, as if reality hid behind a veil where we could see shadows and shapes, but not the actual details. In design practice, this means that aesthetics emerge from our interactions with other objects, giving us insight into what those objects represent. These aesthetics emerge from feedback.

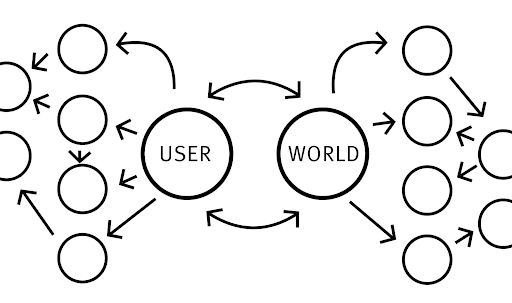

As opposed to a subject-object ontology (as described earlier), design’s approach is pluralistic. A pluralistic approach to design looks at the way objects interact with each other at all scales. When an individual’s behavior is nudged, a pluralist might focus less on the outcomes that emerge from their interactions. Instead, they might also ask: how does this affect the individual internally, and also, how does this affect the other systems that individual interacts with (See Figure 1)?

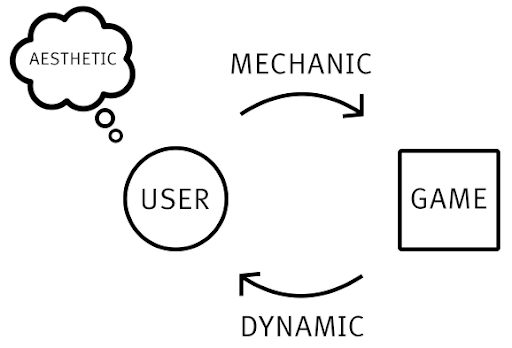

Aesthetics emerge from these complex, emergent interactions that defy our predictive frameworks. Design expresses this in many different ways throughout its varied fields. Game design uses the Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics (MDA) framework to describe complex interactions and the aesthetics that emerge from them.

Figure 2 is a representation of the MDA framework, which can be summarized as:

- The player interacts with the game using a mechanic (run, jump, swim)

- The system responds to the player, creating a dynamic

- The player then feels something based on this feedback. This is where the aesthetic emerges.

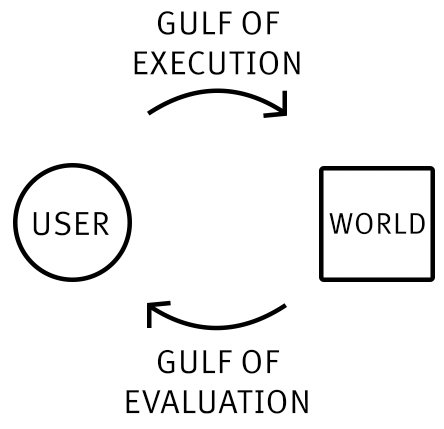

Human-Computer Interaction teaches a similar concept represented by the Gulfs of Evaluation and Execution. In this approach (pictured in Figure 3) the user interacts with the world, and both the execution and evaluation points are mediated by a gulf that separates them.

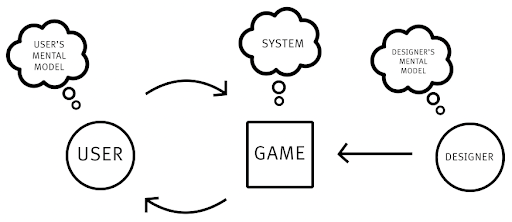

In his seminal design book The Design of Everyday Things, Don Norman describes yet another similar approach, and further elaborates on the concept by introducing mental models. In many ways, mental models emerge from the same dynamics that aesthetics emerge from according to the MDA framework.

Aesthetics cannot be completely explained by science because they are withdrawn beyond the gulf. One can only describe outward manifestations of aesthetics (a smile, grimace, appearances of excitement in an individual), because aesthetics emerge from inside the objects (our thoughts and feelings in reaction to stimuli). The inward nature of aesthetics means they are not transparent outwardly, but are intentionally reflective inwardly. That is, when you interact with a smartphone, the description of that interaction cannot simply be reduced down to a series of button presses, screen swipes, and success criterion -- rather, the interaction is also your feelings of delight, surprise, and wonder that cannot be discerned except from within.

Design and Science

Science has long informed design, as have art, philosophy, and religion. Importantly, while design incorporates concepts from science and other fields, it is its own distinct practice from these other fields. Where art abstracts through metaphor, design specifies through reduction, and where science reduces, design abstracts through metaphor. Design exists in the liminal space between abstraction and reduction.

We see science’s influence upon design in, for instance, Human–Computer Interaction (HCI), which is predicated upon concepts such as cognition, perception, and understanding. We see it in graphic design when we discuss how people perceive and understand color and the physiology of the reading process which determines the conventions of typesetting. And we see it in user experience and user interface design when we discuss how people read a website or understand information presented to them in an app. How we display information in design is often based on our understanding of how we know the human brain works, and how the brain will perceive that information.

Nudge, then, attempts to find a home in the design practice, as its roots in behavioral science share the same underlying principles of this reductionist, scientific approach. That is, understanding human behavior as a science informs design methods of many practitioners, and science as a practice attempts to explain the world by reducing it to its constituent components.

Yet design’s foundation is grounded in aesthetics. As opposed to science, which is reductive, the study of aesthetics abstracts upward. The study of aesthetics (in both art and philosophy) tells us that understanding cannot simply be reduced to the constituents of things, but is also constructed through metaphor. Aesthetics is a subjective field of exploration that, contemporarily, has received less attention than scientific (explanatory) methods of design -- ones focused on outcomes over process.