Design and Choice Architecture Frameworks

Nudge appears in design in many ways. In academic literature, there are many proposed methods for implementing it.

In Nudge Your Customers Toward Better Choices, a piece published in the Harvard Business Review (HBR), Goldstein et al. argue that there are two kinds of nudges in product design: mass defaults and personalized defaults. Put differently, there are nudges in product design that can apply to all of your customers, and defaults that can be designed into products that cater to groups or individuals through data collection and recommendations. Nudges are not necessarily behavioral changes aimed at broad groups, then, but can be applied to individuals. This would seem to require more than common heuristics that the authors of Nudge have anticipated, since individual preferences (whether it’s your favorite food, color, or dislike for the TV show Hogan’s Heroes) would also need to be considered. A choice architect in this instance would not be an expert on group preferences, but somehow, needs to be an expert on your preferences.

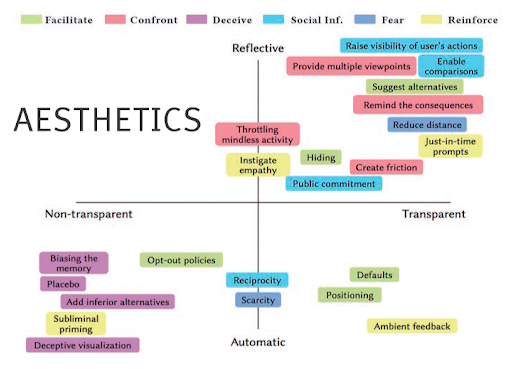

Another approach to choice architecture in design is outlined in 23 Ways to Nudge: A Review of Technology-Mediated Nudging in Human-Computer Interaction. In it, Caraban et al. create an elaborate framework that outlines 23 distinct mechanisms of nudging, grouped within 6 categories, and leveraging 15 different cognitive biases. The six categories range from confrontation (“nudges that pause an unwanted action by installing doubt”) to deception (or, nudges that “use deception ,.. in order to affect how alternatives are perceived ... or experienced, with the goal of promoting particular outcomes”). Significantly, the piece takes a very prescriptive (see: scientific) approach to including choice architecture in design. As we have noted earlier, it’s this prescriptive nature that makes it difficult to fully reconcile choice architecture with design.

The authors elaborate on this work with a later piece introducing a “Nudge Deck” -- a design tool meant to help designers who are implementing nudges in their own work -- a kind of nudge of its own. The deck of cards -- in much the same way as science prescribes a course or set of actions that must be followed -- instructs designers to use the deck in order to incorporate nudge responsibly into design. So, nudges can be targeted at groups or individuals. We can do so in a way that is prescriptive, and that will result in best outcomes for that group or individual. If designers follow a series of steps provided, they can nudge in an ethical manner.

In parallel with literature on how to think about choice architecture in design, studies have been conducted on its efficacy in design.

In Nudge & Influence Through Mobile Devices, Eslambolchilar et al. propose a workshop that argues mobile devices are well-situated toward facilitating nudges because they are able to collect data on their owners, in situ, which in turn could be used to influence habituated behaviors. Central to the authors’ assertion is the concept of peer influence (“comparing individual performance with relevant social group performance [and] social network sites running on the device facilitate communication of personalized descriptive social norms that relate to the participant’s self-defined community.”). We see, again, that nudges can be targeted based on data collected from an individual. Problematically, the authors in this case also conflate nudge and choice architecture with social architecture -- particularly, that of mobile and online social networks. But social networks are built on what and who we know, and therefore limit our choices by creating echo chambers -- nudges, in this case, would only come from a limited selection of options that our own networks provided us with.

Choice architecture and social media seem to be a topic of interest in design. In Nudge for Deliberativeness: How Interface Features Influence Online Discourse, Menon et al. conducted a between-subjects experiment to determine how nudging could mitigate invective in online discourse. The nudges used to influence behavior of the participants were: Partitioning Text Field, Reply Choice Prompts, and Word Count Anchor. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the nudges seemed to actually increase the number of arguments that people made. The only nudge that seemed to have a positive effect was the Reply Choice Prompt asking people if they wanted the original poster to reply to their argument. The authors admit that the social pressure might, however, reduce creativity and reduce peoples’ willingness to speak their minds.

There is, then, a prescriptive way to apply choice architecture to individuals or groups. That prescription can be administered in many ways, including through social media, which can be used as the mechanism to enforce change (through peer pressure, etc). It is at this point that we must ask: where is the design in choice architecture and nudge? This methodology seems more like a social scientific approach to human behavior than it does an aesthetic one.

Design and Nudge are Incongruent

Caraban et al. (referenced earlier) assert that there are 23 distinct manifestations of nudge in design. In 23 Ways to Nudge, a list of nudge types are plotted along axes representing transparency to user (non-transparent to transparent) and response elicited from user (reflective to automatic, explained more below). See Figure 5.

First, the authors argue that dark pattern, or ethically questionable, nudges fall within the automatic and non-transparent quadrant. These nudges might aim to deceive or trick the user by taking advantage of their brain’s automatic response systems while hiding a nudge’s true intentions. Social media companies are notorious for these kinds of nudges, or dark patterns, when their algorithms intentionally incentivize emotionally manipulative content in order to increase attention and engagement. In this case, the nudge (content that will incite anger) is not transparent to the user, while the response (anger) is automatic.

Conversely, positive or benign nudges fall within the reflective and transparent quadrant. These kinds of nudges remind, suggest, or demonstrate possibilities. When your music player suggests songs based on your preferences, this is a positive nudge that demonstrates or suggests other possibilities, leading you down a path toward additional discovery of songs. The nudge is reflective, in that it offers choices without coercion, while being transparent in its actions (“You might also like…”).

Finally, we have the puzzling automatic and transparent quadrant. An automatic and transparent nudge might be something done without the user’s explicit approval, but is transparent in its intent and typically gives the user the ability to change it. Default settings on a smartphone and ambient feedback are some such examples. A phone, by default, might be set to provide automatic updates for security purposes. Yet the user of the phone also has the ability to turn these settings off through a transparent settings panel if they no longer wish to partake in automatic updates.

This leaves us with one quadrant empty. A keen observer may have noticed that none of the nudge types fall within the reflective and non-transparent section of the chart. But what is a reflective and non-transparent act? One might assume that it is something that elicits thought from the user, but does so in a way that eludes perception.

It seems curious to develop a four-quadrant model with one quadrant entirely empty. What fits there?

Going back to an earlier assertion, we know that aesthetics are not transparent and are inwardly affecting. One of the most recognized pieces of music to come from the Agnus Dei section of Roman Catholic Latin mass is the round Dona Nobis Pacem which translates to “give us peace.” The song is often sung during Christian Holy season as a call to unification. But it also has a secular history, such as when it was sung in the streets during the reunification of Germany by many who were likely unaware of the song’s literal text, but who understood its intent.

Like most art, Dona Nobis Pacem eludes literal understanding -- its contents are not entirely transparent. But understanding the literal piece is also unimportant, as demonstrated by its adoption from those who didn’t even understand its words, but understood its intent. The song, then, is able to inwardly affect those who hear it while eliciting a reflective response. Looking back at Figure 5, aesthetics seem to fit nicely, then, into a quadrant that is non-transparent and reflective. Dona Nobis Pacem, Van Gogh’s Starry Night, and yes, even the objects of design channel aesthetics to evoke these reflective and non-transparent effects. If the authors of 23 Ways to Nudge are correct, then, nudge does not manifest itself in this quadrant because it is incongruent with aesthetics.

If nudge is incongruent with aesthetics, and if aesthetics is a central feature of design, then nudge is also de-facto incongruent with design.